CHEN CHONG SWEE

(1910 - 1985)

Source: Singapore Watercolor Society

He was an artist, teacher

and writer. He had major influence in the development of Singapore art. He was

the first in attempting a synthesis of distinctive aesthetic traditions of the

East and West through pioneering the style known as “Nanyang School” Chinese

painting style.

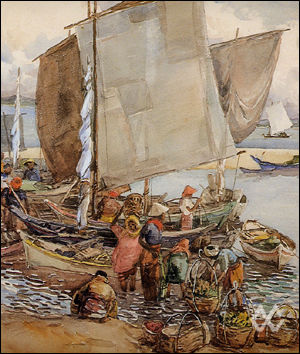

Mr. Chen Chong Swee is one of the Singapore Watercolour Society founding members

and was the treasurer for many years. His painting subjects were often composed

from his surrounding environment and daily life activities for he believed that

a painting must be understood and be a recollection of one’s thoughts. The many

inspirational masterpieces were form his numerous tours to Bali and East Coast

of West Malaysia.

Source: Living2000 - the Cape of Good Hope Gallery

1910 Born in Chenghai County, Guongdong Province, China.

1931 Settled in Singapore.

1985 Passed away in Singapore.

Education

1929 Graduated form Union High School, Shantou, China.

1931 Graduated from Xinhua Arts Academy, Shanghai, China.

Experiences

1935 Co-founded Salon Art Society, now known as the Singapore Society of Chinese

Artists.

1936-75 Lectured Art at :-

Jit Sin Chinese Public School, Penang

Chung Hwa School, Malacca

Tao Nan School, Singapore

Tuan Mong High School, Singapore

Chinese High School, Singapore

Chung Cheng High School, Singapore

Teachers' Training College Singapore ( now The Institute of Education,

Singapore)

Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, Singapore

1969 Co-founded The Singapore Water Colour Society.

1960-80s Served as member of the Selection Committee of Annual Singapore

National Day Art Exhibition. Served as adviser to :-

Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, Singapore

Life Art Society, Singapore

San Yi Finger Painting Society, Singapore

Singapore Teachers Art & Craft Association

Served as President & Vice President of :-

Singapore Society of Chinese Artists

Singapore Water Colour Society

Singapore Art Society

Awards

1935 Cash award, King George V Silver Jubilee Art Exhibition.

1965 Meritorious Public Service Star of the Republic of Singapore.

Exhibition

1932-80s Participated in various local art exhibition including the yearly

national day art exhibition and the yearly exhibition of the various art

societies.

Selected to represent Singapore in various overseas exhibitions.

1984 Chen Chong Swee Retrospective, presented jointly by the Ministry of Culture

and the National Museum, Singapore.

1993 Chen Chong Swee, His Thoughts, His Art, presented by the National Museum,

Singapore.

1998 Passages, selected works of Chen Chong Swee, presented by National Heritage

Board, Singapore Art Museum.

Publications

1983 The Paintings of Chen Chong Swee - published by Nan Fong Art Company.

1984 Chen Chong Swee Retrospective 1984 - published by the National Museum,

Singapore.

1993 Chen Chong Swee : His thoughts, His art - published by the National Museum,

Singapore.

1994 Chen Chong Swee Charity Auction, published by Sotheby's Singapore.

Educational Endowment Fund

1995 Established Chen Chong Swee Art Scholarship Fund, Managed by the National

Art Council, Singapore.

Chen Chong Swee : HIS THOUGHTS

Source: by Kwok Kian Chow 1993

In the first monograph on the history of art in Singapore and Malaysia, A

Concise History of Malayan Art published in 1963, Ma Ge wrote that Chen Chong

Swee had received so much recognition for his art to the degree that it

overshadowed his significant contribution to art education.' In an article of

the same year, Cao Shuming quoted Ma Ge to call attention to Chen’s important

work in art education and publication.

Chen Chong Swee was a prolific writer. He frequently contributed articles to

newspapers, exhibition catalogues, and magazines published by art associations.

These articles contain discussions on aesthetic issues such as the Fundamental

differences in Chinese and Western art, the functions of art education, and the

need to develop an ink painting relevant to a multicultural environment. These

writings provide a wealth of resources not only for understanding Chen’s art

theories, but also For characterising the art discourse in Singapore From the

1940s to the 1970s.

In the history of Singapore art, Chen Chong Swee has been acclaimed as the first

artist to incorporate local subject matters in the traditional Chinese ink

painting.’ Chen’s first attempts to incorporate Malay kampong scenes in ink

painting was duly noted in Ma Ge’s monograph. T. K. Sabapathy sees the impetus

of the Nanyang Style, the first art movement in Singapore in which Chen was

among the key pioneer artists, as a cross-fertilisation between the Chinese

painting traditions (the "scroll") and the School of Paris (the "easel"). The

spirit of the School of Paris – in its celebration of the artist as a Free and

bold creator of new visual languages – stimulated not only the Chinese artists

in the 1920s and 1930s, but also the Nanyang artists as they emerged from the

Former context (Chen and others were graduates of art academies in Shanghai in

the 1930s) to face the challenges sec by the new Southeast Asian environment.

Chen Chong Swee’s path to modernize and localize ink painting was a long and

difficult one. His writings over the years provide a glimpse into the complex

theoretical platform mounted as a foundation For what appeared as a mere

divergence in the depiction of subject matter in ink painting. In the tradition

of Chinese art theoretical writings since the beginning of this century, such a

discussion had to begin by addressing the fundamental differences in Chinese and

Western art.

In an article which Chen wrote for the 1948 annual of the Society of Chinese

Artists, he noted that since the days of Maneo Ricci, the Jesuit scholar who

brought Western religious images to China in late 16th-to early 17th-century,

the introduction of Western art into China was marked by a series of failures,

such as the unconvincing works of Lang Shi’ning (Giuseppe Castig-lione, 1688 –

1766). Chen suggested that instead of the Westernization of Chinese art, it

would be more fruitful to view the development in Western art since

Impressionism as reaching towards the aesthetic ideals of the traditional

Chinese ink painting. This process is seen in the Western painting’s increasing

emphases on the subjective in artistic intentionality, linearity in pictorial

expression, and the preference for extra-worldly subject matters, such as Paul

Gauguin’s paintings on Tahiti.

In a 1961 article, Chen noted that the fundamental difference in Western and

Chinese art may be discerned through the distinction between Western and Chinese

art historical methodologies.’ Chen commented that for Western art, historical

categorisation was based on aesthetic attitude and the subject matter of the art

works: "The celebration of the revival of the Greek and Roman spirit was known

as Neo-Classicism..., the depiction of heroes and beauties with idealistic

passion was known as Romanticism..., painting purely landscape was

Impressionism... , and pictorial exaggerations based on subj ectivity was

Post-Impressionism..."’ Chinese art history, on the other hand, did not

categorize according to such criteria: "Whether it was the Northern School of Ma

(Yuan) and Xia (Gui), the Southern School of Dong (Yuan) and Ju(-ran), the

bonelessXu (Xi) and Huang (Quan), and even the academic painting, the

literati...; despite their categorical differentiation, they all comprised a

very wide range of subject matters; the pictorial expressions were varied, but

the aesthetic ideal was the same." This aesthetic ideal was Xie He’s Six

Principles which Chen discussed in greater detail in his other articles (see

below).

A further elaboration of the fundamental distinction between Chinese (the term

"Eastern" was used in this article) and Western art was featured in the 1965

Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts graduation magazine: "Eastern art is abstruse while

Western art is practical; Eastern art is synthetical while Western art is

analytical... Chinese painting emphasises the spirit resonance (see below) while

Western painting emphasises the feeling of texture; The Chinese stress the ties

of friendship in the conduct of human affairs while the Westerners place

emphasis on ‘reason’... This is the difference between Eastern and Western

cultural dispositions... Today, as means of communications are advanced and

sophisticated, there should be a greater exchange of Eastern and Western

cultures to enhance mutual integration; Art transcends boundaries that separate

nations and facilitates understanding between people."

Chen Chong Swee regarded the unchanging aesthetic ideal in ink painting

tradition to have its bases on the Six Principles. Based on Osvald Siren’s

translation of the original 5th-century Xie He’s text, the Six Principles

are:

The first is: Spirit Resonance (or, Vibration of Vitality) and Life Movement;.

The second is: Bone Manner (i.e., Structural) Use of the Brush;

The third is: Conform with the Objects to Give Likeness;

The fourth is: Apply the Colours according to the Characteristics;

The fifth is: Plan and Design, Place and Position (i.e., Composition);

The sixth is: To Transmit Models by Drawing.

Chen wrote in an inscription on his painting, A Village Scene (1974):

What may be considered as a true painting is one that is able to capture

thoroughly both the appearance and fundamental elements of a physical form. The

reason why the Six Principles are the (unchanging) principles, it is precisely

because of this (thoroughness).

In subsequent lines, Chen emphasized the need to apply the Six Principles

according to the requirement of the subject matter of the painting. In painting

Southeast Asian subject matters, the unchanging principles should be applied,

though without restricting oneself to the traditional ink or brush methods:

By employing the traditional cun-textural ink methods, one can hardly bring out

on paper the greenery, lush and luxuriant splendour of landscapes in South-east

Asia. An integrated approach, incorporating the techniques of various schools of

painting, is therefore adopted for this purpose – never mind the mixing-up of

the Northern and Southern accents.

Chen apparently came to his decision to adhere to the Six Principles after

attempts to incorporate chiaroscuro method in ink painting. The following

inscription is found on a 1950 painting, A Kampong:

In painting scenes of South-east Asia, I employ mainly techniques of Chinese

painting. The use of yinyang (chiaroscuro) approach for this painting is my

first attempt of this kind. This is not to be repeated as it is against my

principle.

In the scheme of the Six Principles, Chen regarded (1961) the contribution of a

Western art learning to ink painting was restricted to the third principle,

"Conform with Objects", i.e., representational methods." It was important for a

student of ink painting to fully comprehend all the six principles in order to

create good ink works.

In teaching ink painting, on the other hand, Chen Chong Swee elevated

representational method to a position of foremost importance, a point of

contention between him and Chen Wen Hsi who did not agree that ink painting

should first be learnt through painting from nature." Chen Chong Swee’s emphasis

may be understood in the context of what he conceived to be the purposes of art

(1968):

Art is a part of life and cannot exist independently from real life. Art must be

objective. If it fails to be accepted by another person, it loses its essence of

universality and can no longer exist as art. If a work of art fails to embody

truth, goodness and beauty, it cannot be regarded as a true work of art.

Evocation of sympathetic understanding in others by aesthetic means is the

fundamental task of an artist.

In addition to sympathetic understanding, evoking in others a sense of

admiration and appreciation of our life appropriately beautified by art, is a

brilliant technique of an artist.

Furthermore, in addition to a sense of admiration and appreciation, evoking in

others empathy with our life by aesthetic means so that they may, together with

you, be steeped in the vision of beauty, is the mission of an artist.

Chen’s realist position in art had been consistent. In an earlier article

(1960), he stressed the communicative function of art:

If you are an artist and do not want yourself kept within the confines of an

ivory tower, you will be able to appreciate the social value of the arts. A

great work of art does not end at the superficial stage of artistic decoration.

The arts are about using the subtle aesthetic influence to evoke empathy in

people. We must bear in mind that the arts serve as a bridge of communication,

in ideas and emotions, between people. Only a vibrant work is a living work of

art, widely accepted as such by the people.

Whereas the aesthetic ideal of Chinese art based on the Six Principles would

always remain constant, Chen’s proclamation on the communicative function of

art, on the other hand, was based on a concept of art historical evolution. Chen

saw (1947) the visual arts in the feudal society as a plaything of the ruling

classes and the socially privileged literati. Art was denied to the ordinary

people. This was the condition within which Chinese art developed. Chen

recognised (1973) the time of the Eight Eccentric Painters of Yangzhou

(18th-century) as an important demarcation in Chinese art history:

The Eight Eccentric Painters of Yangzhou of Qing dynasty sought to protest

against artists of that time who served only the affluent and the influential

class, who eulogised the "Emperor" and even stooped servilely to be honoured and

titled, who voluntarily abandoned the independence of the arts and reduced the

arts to "offerings to the Emperor". The reason why the Eight Eccentric Painters

of Yangzhou were praised and well received by the people at that time was that

they freed themselves from the fetters of the arts and returned to the embrace

of the "people", meaning mainly scholars of that time. Domination of the arts,

shifted from the rich and influential class to the scholars, did bring some

changes in form and content.

The contemporary art historical phase was a further development from the time of

the Eight Eccentric Painters of Yangzhou:

In a world enjoying freedom of thinking and speech, unreasonable phenomena,

kindness or degeneration of society, tragedies or comedies of the mortal world,

heroic and moving deeds, could all be expressed fully through different art

forms. The era of the Eight Eccentric Painters of Yang-zhou, with its prosperity

for ambiguity and sentiments implicit in objects and poems, is over.

In the current period of Freedom of expression, it would follow that ink

painting should no longer be "crossing the bridge on the donkey, fishing in the

winterly lake, and the sounds of the old temple bell...; if during the Song

dynasty there was Life Along the River on the Eve of the Qingming Festival (by

Zhang Zeduan, late 11th- to early 12th-century), why shouldn’t we have a

painting like ‘Life Along the Singapore River’ ?" Below are two proposals by

Chen on the renewal of ink painting written in 1967 and 1974 respectively. The

earlier version is more passionate and confrontational:

What should be the content of our ink painting in view of the change in social

and geographical circumstances? I propose:

(1) The depiction of actual sceneries. Although my own experience tells me that

capturing aeroplanes, atomic bombs, bungalows and tarred roads in ink painting

is not easy, we do need to find a way...

(2) The merger of literature and painting as a basic characteristic of Chinese

art must be preserved. However, why not feel free about adding English or Malay

inscriptions to ink painting in order to enhance its appeal.

The later version is more subdued, but with a tone of certainty following his

further experiments in ink painting:

I propose:

(1) Techniques of Western art should be incorporated;

(2) New subject matters should be accommodated;

(3) Modern life should be depicted.

Chen continued with specific recommendations on the preservation of the

traditional spirit in Chinese painting:

(1) The various traditional formats of ink painting such as the hanging scroll,

hand scroll and album leaf should be preserved;

(2) Linearity should be the basic structural element of painting, supplemented

by colour; in the case of boneless works, the brushwork should revolve round the

structural forms and the application of colour should be sprightly and clear to

avoid resemblances to watercolour; [cf. Xie He’s second principle: Bone Manner]

(3) Objects in painting should harmonize with one another;

(4) Voids and solids should be well balanced in the composition; [cf. Xie He’s

fifth principle: Plan and Design]

(5) Painting should be implicit rather than explicit;

(6) Painting should convey a literary perspective which is characteristic of

Chinese art.

Chen Chong Swee was a leading artist, art educationist, and arts writer in

Singapore in the 1940s to 1970s. The current essay has thus far attempted to

delineate the theoretical infrastructure that supported Chen’s endeavours to

modernize and localize Chinese ink painting: from Chen’s concept of the

fundamental differences in Chinese and Western art, the Six Principles perceived

as the constant aesthetic ideal of Chinese art, the social purposes of art, to

Chen’s concept of art historical evolution which supported his view of

contemporary art as having a communicative function.

Chen’s writings on art are not limited to the above topics discussed. His

writings also serve as important primary sources for Singapore art history. His

most comprehensive article on Singapore art history is Singapore Art Circle in

the Past Four Decades: A Retrospective (1969) which has a section on the visual

arts in Singapore in the late 1920s. Mention was made of the Nanyang shuhuashe

("Nanyang Society of Calligraphy and Painting") founded in 1929 as the first art

society in Singapore and Malaysia." In the same article, Chen also discussed the

visual arts activities of the Japanese residents during the Japanese occupation

of Singapore, the growth of caricature practice and the advertising industry in

Singapore. The inclusion of the above topics demonstrated Chen Chong Swee’s view

of art history as unrestricted to the traditional categories of painting and

sculpture.

In the same article, Chen also wrote on Le Mayeur, the Belgian artist who

resided in Bali and who exhibited in Singapore in the late 1930s. Le Mayeur’s

images of Bali would have influenced Singapore artists’ perception of Bali and

were important visual sources for the Singapore pioneer artists prior to their

historical field trip there in 1952. Chen wrote:

A Belgian artist who settled in Bali put up an art exhibition in Singapore in

1938 (?). This Belgian artist originally wanted to go to Tahiti as he had a

yearning for the type of life led by the Post-Impressionist artist Gauguin. On

his way there he passed through Bali and found that there was no place on earth

like Bali – its dancing and singing so soul-stirring and its women so vigorous

and graceful. Hence, he settled down at the stretch of Bali beach fronting the

Indian Ocean. As the standard of living in Bali was very low, the proceeds from

the sale of a few paintings were enough to support him for a few years. It was

around the summer of 1938 that he held a second art exhibition in Singapore.

Before the opening of the exhibition, the Belgian consul held a reception on his

behalf for people in the art circle at a house at Holland Road. I remembered

seeing many large landscape paintings of his done during his travel in India.

His works were executed with free-flowing and bold, strong strokes, in bright

and gay colours. Figures dominated his Bali paintings. His works, be they

sketches done in light colours or bright-coloured oil paintings, showed that

they were inspired by the bright and clear tropical sunlight. His brightly-clad

energetic and graceful dancers, dancing to the beat of the drums and bells, or

his weaving women, kneeling beside the loom weaving sarong cloth, fully

demonstrated the tranquil and fine life of the Balinese. The painting partner

(who later became his wife) he brought along, attired in traditional Balinese

costumes, was on hand to receive guests. She offered herself for photographs

bare-breast. This created quite a stir in Singapore.

During the 1952 Bali field trip Chen Chong Swee made with Chen Wen Hsi, Cheong

Soo Pieng and Liu Kang, Chen drafted an unfinished essay, A Profile of Bali.

Chen wrote that the Dutch in promoting Bali as the paradise on earth to generate

revenue from tourism marketed the island internationally as "Eden, Gem Island,

Island of Poetry, Island of Dream, etc." The term, "Nudist Empire" was popular

then amongst people in Nanyang. Prior to visiting Bali, Chen was told a vulgar

description of Bali as a place where there were women with breasts so huge that

they would knock an approaching pedestrian off the road. "Although this is a

joke," Chen wrote rhetorically to turn this description into acknowledging the

elegance of Balinese women, "it is a fairly accurate description of Bali; Bali

is indeed a women’s empire; the robust beauty of Balinese women and the pastoral

scenery form an excellent painting." Chen and company stayed in Bali for more

than three weeks and visited many locations on the island. They also attended a

flamboyant Balinese cremation ceremony and spoke with many Balinese, "from

royalties to women and children in the villages.

On another occasion Chen wrote (1965) about women artists. Chen noted that they

had been many important women artists in Chinese cultural history who did not

subject themselves to the feudal edict that women without talents and skills

were virtuous. Chen commented that given half of human kind were women there

were, however, proportionately too few prominent women in all fields. Chen

commended the Chinese Women’s Association for its visual arts programmes which

provided women opportunities to participate in cultural activities.

Chen Chong Swee was a keen observer and writer in all aspects of visual arts

culture. Chen praised the work of Pablo Picasso. He lamented on the low priority

given to art in formal education. Chen commended on-the-spot art competitions

but questioned aspects of art exhibition practices in Singapore. Chen discussed

the need for a national art gallery and collection, and a national art built

upon the Western, Chinese and Indian civilizations.

In Chen Chong Swee’s writings, it is observed that Chen was an artist deeply

concerned with the larger issues of visual culture and art history. In Ma Ge’s A

Concise History of Malayan Art, the author identified Chen Chong Swee, together

with Liu Kang, Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Wen Hsi, Georgette Chen Li Ying, Lim Cheng

Hoe and the Penang artist, Chuah Thean Teng as the pioneer artists in shaping a

Malayan consciousness in the visual arts. Drawing reference to Lim Hak Tai, the

founder of the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts’s notion of Nanyang Art, T. K.

Sabapathy and others have identified the former six artists to be the pioneer

artists of the Nanyang Style. The Nanyang Style as an art historical topic will

continue to be discussed for a long time to come. Chen Chong Swee played a

pivotal role in both the visual linguistic and art theoretical formation of the

Nanyang Style. Chen, in fact, went further to deal with universal issues such as

the purposes of art and the modernisation of ink painting.